Knowledge distillation

Knowledge distillation has become a cornerstone technique for training capable smaller language models. The recipe seems straightforward: generate high-quality responses from capable teacher models, then train a student model on these examples. Unfortunately, student models learning from knowledge distilled from multiple capable teachers don't necessarily perform well, mixing responses from multiple teacher models often produces worse results than using a single teacher*, even when each individual teacher is highly capable.

This phenomenon, sometimes called the "knowledge conflict", "style inconsistency", or "teacher heterogeneity" issue, has been observed repeatedly and is open knowledge in frontier labs, but remains underexplored in the literature.

The Empirical Observation

Recent work has documented the multi-teacher distillation problem directly. Jin et al. (2026) found that "contrary to expectation that enlarging the teacher LLM ensemble would enhance the capabilities of student models, the distillation performance actually declines as the number of teacher models further increases". This decline persists even when each additional teacher is individually capable.

The PerSyn paper similarly observes that "stronger models are not always optimal teachers for small student models, since their outputs may be overly complex and shift away from the students' distribution". Simply mixing synthetic data from multiple teachers leads to suboptimal performance.

But why? Each teacher produces correct, high-quality responses. Shouldn't more diverse training data help?

The Distributional Perspective

To understand what's happening, we need to think about what the student model is actually learning during supervised fine-tuning (SFT).

Single Teacher: A Coherent Target

When training on data from a single teacher, the student learns to approximate that teacher's output distribution:

The teacher's distribution, while complex, is coherent—it reflects a single model's learned patterns for formatting, hedging, explanation structure, and stylistic choices. The student has a clear target to fit.

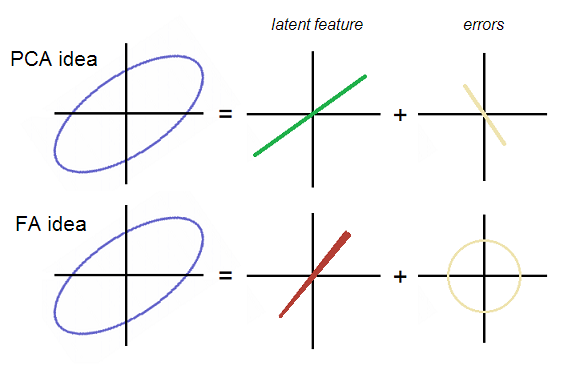

Figure 1: With a single teacher, the student learns to approximate a unimodal distribution. The optimization objective is clear.

Multiple Teachers: Superimposed Distributions

When training on data from multiple teachers, the student sees a mixture:

If the teachers have different stylistic patterns—different ways of starting explanations, different hedging phrases, different levels of verbosity—then the training distribution is multimodal. The student must fit multiple overlapping but distinct distributions simultaneously.

Figure 2: With multiple teachers, the training distribution becomes multimodal. Each teacher contributes a distinct mode.

What Does the Student Actually Learn?

SFT with cross-entropy loss on multimodal data tends to produce an interpolated distribution.

When the student model lacks the capacity or signal to separate the modes, it learns something like the average:

This interpolated distribution may not correspond to any coherent generation behavior. It places probability mass in regions between the modes—outputs that neither teacher would produce.

Figure 3: The student learns an interpolated distribution that doesn't match any individual teacher. The resulting outputs may be incoherent—blending styles in ways no real model would.

Concrete Example

Consider how different models explain a mathematical concept:

Teacher A (Concise):

"The derivative of x² is 2x. This follows from the power rule: d/dx[xⁿ] = nxⁿ⁻¹."

Teacher B (Verbose):

"Let me walk you through finding the derivative of x². We'll use the power rule, which states that for any function f(x) = xⁿ, the derivative is f'(x) = nxⁿ⁻¹. Applying this with n=2, we get d/dx[x²] = 2x²⁻¹ = 2x. This is our final answer."

A student trained on both might produce:

Student (Interpolated):

"Let me explain. The derivative of x² is 2x. We use the power rule."

This response is neither the clean conciseness of Teacher A nor the thorough walkthrough of Teacher B. It's an awkward middle ground that represents neither distribution well.

What to do instead?

While many different distillation methods have been presented in the literature for multi-teacher knowledge distillation, many involving clever weighting and estimation of teacher models and their "expertise", the leading open-source model developers—DeepSeek, Qwen, Kimi, and others—have converged on a pattern that sidesteps this problem: specialist models derived from the same base model.

The Specialist Distillation Pattern

The general recipe, as observed in multiple model releases:

- Train base model on large-scale pretraining data

- Create specialists by fine-tuning the base on domain-specific data (math, coding, reasoning, etc.)

- Generate training data from specialists on prompts in their respective domains

- Train general model by distilling from all specialists back to the base

Crucially, all specialists share the same base model. This means they share:

- The same vocabulary and tokenization

- Similar underlying representations

- Consistent formatting tendencies inherited from base training

- Related but not identical output distributions

Figure 4: Specialists from the same base model have distributions that are shifted versions of each other, not entirely different distributions. The interpolation problem is greatly reduced.

Why Same-Family Specialists Work

When specialists derive from the same base:

- Distributional similarity: Their output distributions are perturbations of a shared prior, not arbitrary distributions

- Style inheritance: Domain-specific fine-tuning changes what the model knows more than how it expresses things

- Bounded divergence: The amount of post-training data for specialization is small relative to pretraining, limiting distributional drift

- This also gives insight to the scale of data that is needed to overcome the knowledge conflict problem when distilling from multiple teachers, which is likely bigger than that of typical SFT data size.

The student learning from same-family specialists isn't trying to fit arbitrarily different distributions—it's fitting distributions that are already close in the space of possible outputs.

The Motivation: Why Not Just Mix All the Data?

A natural question arises: why go through the trouble of training separate specialists and then distilling? Why not simply combine all the domain-specific training data and train a single model on the mixture from the start?

The two-stage specialist approach offers several advantages:

-

Avoiding catastrophic forgetting during training: When training a single model on mixed data, aggressive optimization on one domain can degrade performance on others. Specialists can be pushed harder on their specific domain without this concern.

-

Flexible data ratios at distillation time: With specialists, you control the mixture ratio when generating synthetic data, not when training. This is a much easier hyperparameter to tune—you can regenerate data at different ratios without retraining models.

-

Domain-specific training techniques: Different domains may benefit from different training approaches (curricula, loss functions, data augmentation). Specialists allow domain-specific optimization that would conflict if applied simultaneously.

-

Independent quality control: Each specialist can be evaluated and iterated on independently. If your math specialist underperforms, you fix it without touching the code specialist.

-

Selective distillation: The distillation process can cherry-pick the best outputs from each specialist via rejection sampling. Direct data mixing doesn't offer this quality filtering opportunity.

-

Compute efficiency for iteration: Updating one capability requires retraining only that specialist and regenerating its contribution to the distillation data, not retraining the entire model.

-

Organizational simplicity: Each specailist model can have a separate team associated with it in the organization, simplifying human communication overhead.

The key insight is that the distributional consistency comes from the shared base model, not from training on mixed data. Specialists diverge in what they know, but retain similar patterns for how they express it—making their outputs compatible for distillation even though they were trained separately.

Evidence from Practice: The DeepSeek-R1 Example

The DeepSeek-R1 paper provides a particularly clear example of this pattern applied to reasoning. Their pipeline:

-

DeepSeek-R1-Zero: Apply large-scale RL directly to the base model (DeepSeek-V3-Base) without SFT. This produces a specialist reasoning model with emergent chain-of-thought behaviors—but also issues like poor readability and language mixing.

-

Rejection sampling: Generate reasoning solutions from R1-Zero, filter for correctness.

-

Combined SFT: Train the final R1 model on a mixture of:

- Reasoning data from R1-Zero (the reasoning specialist)

- Non-reasoning data from DeepSeek-V3's existing SFT data (writing, factual QA, etc.)

Critically, both the reasoning specialist (R1-Zero) and the non-reasoning data source (V3) derive from the same base model. The paper explicitly notes that "we create new SFT data through rejection sampling on the RL checkpoint, combined with supervised data from DeepSeek-V3 in domains such as writing, factual QA, and self-cognition."

- the reasoning patterns come from one specialist (R1-Zero),

- general capabilities from another (V3's post-training)

Both share the V3-Base foundation. The result maintains coherent outputs while gaining specialized reasoning abilities.

- Qwen follows a similar iterative improvement loop with domain specialists

- The general model benefits from domain transfer while maintaining coherent outputs because all teachers are consistent stylistically.

Connection to Reasoning Mode Training

The rise of "thinking" models—those with explicit reasoning traces enclosed in <think> tags—introduces a new dimension to this problem.

Reasoning as a Separate Distribution

Models like DeepSeek-R1, o1, and Claude's extended thinking learn two distinct output modes:

- Direct mode: Standard assistant responses (System 1)

- Thinking mode: Extended reasoning traces followed by answers (System 2)

These modes have different distributional characteristics. Thinking mode features:

- Longer outputs with self-correction

- Exploratory hypothesizing

- Step-by-step decomposition

- Different transitional, introspective phrases ("Let me reconsider...", "Wait, that's not right...")

Is This Multi-Teacher Distillation?

One might ask: if we train a model to have both thinking and non-thinking modes, aren't we effectively training on two different distributions?

Yes, but with a crucial difference: the mode is explicitly marked.

<no_think_token> → Distribution A (direct responses)

<think_token> → Distribution B (reasoning traces)

The <think> token acts as an explicit conditioning signal. The model doesn't need to infer which distribution applies—it's directly specified. This converts the problem from:

- Implicit mixture (bad): Learn to somehow fit both distributions without knowing which is which

- Conditional distributions (tractable): Learn

and separately

Figure 5: With explicit mode tokens, the model learns conditional distributions rather than a confused mixture. The token boundary provides clear separation.

The Bimodality Hypothesis

This suggests a hypothesis: explicit mode separation via special tokens can allow different "teachers" for different modes.

Specifically:

- Thinking mode could use reasoning traces from a strong reasoning model

- Direct mode could use responses from a stylistically preferred model

- The mode tokens prevent cross-contamination

The student learns:

- Inside

<think>: Reasoning patterns from the reasoning model - After

</think>: Answer style from the preferred model

This is a form of multi-teacher distillation, but the explicit structure potentially makes it tractable. However, this doesn't mean naive application will work in practice. Suppose the model successfully learns to output reasoning process in thie <think></think> block and direct answer outside. The distribution differences between these two modes can be so drastic such that the direct answer doesn't follow from the reasoning tokens. This is not unreasonable -- there's nothing forcing the reasoning logic to "transfer" to the direct answer. Therefore reasoning models trained this way may result in having correct "thoughts" leading to an incorrect answer.

Implications and Open Questions

For Practitioners

-

Prefer single teachers when possible. The simplicity pays off in coherent outputs.

-

If mixing teachers, measure style divergence first. For example, train a classifier to predict which teacher generated a response. High accuracy = high divergence = likely problems. Distilling from the "best math model" and the "best creative writing model" may not lead to the "best math + writing" model.

-

Same-family specialists are safer than arbitrary model combinations. If you must use multiple teachers, prefer those from the same base model.

-

Explicit mode separation helps. If you need different capabilities (reasoning vs. direct), consider explicit mode tokens rather than implicit mixing. There are methods that can improve non-explicit mixed-mode performance though.

Open Research Questions

-

How much style divergence is too much? Is there a threshold below which multi-teacher mixing is safe?

-

Can rewriting normalize styles effectively? Having one model rewrite another's outputs might help, but at what cost to content fidelity?

-

Do larger students handle multimodality better? Perhaps sufficient model capacity can maintain separate modes implicitly.

-

What's the role of data scale? With enough data, does the distributional mismatch problem diminish?

Conclusion

The empirical observation that multi-teacher distillation often underperforms has a natural explanation: training on multimodal data from heterogeneous teachers leads to interpolated distributions that don't correspond to coherent generation behavior. The student learns to produce outputs that fall between the modes—satisfying neither teacher's distribution well.

The research community has responded with practical solutions: using specialists from the same model family, which constrains distributional divergence, and employing explicit mode tokens, which convert implicit mixtures into tractable conditional distributions.

As models become more capable and distillation pipelines more complex, understanding these distributional dynamics becomes increasingly important. Style consistency isn't just an aesthetic preference—it's a fundamental property that determines whether a student can learn coherently from its teachers.