Nov 25, 2025 - Revisiting supervised fine-tuning (SFT) for LLM training

One of the most well-known understanding in the field of LLM currently is that “pretraining is where the model learns knowledge”, SFT and RL then elicit/shapren this knowledge to make them useful. I'm not entirely sure what first popularized this (could just be due to academic diffusion), but the first well-known paper of might've been the LIMA paper (May 2023), which suggests that:

Taken together, these results strongly suggest that almost all knowledge in large language models is learned during pretraining, and only limited instruction tuning data is necessary to teach models to produce high quality output.

This introduced the notion that a model’s capability is upper bound by the quality of the pretraining data, and that the better the pretraining is, the more benefits SFT will be. A corollary of this is that focusing on SFT too much can degrade general model capabilities in other tasks (e.g. reasoning and math).

A later paper, Revisiting the superficial alignment hypothesis (Sept 2024) dispute this:

We re-examine these claims by empirically studying the scaling behavior of post-training with increasing finetuning examples [...] Through experiments with the Llama-3, Mistral, and Llama-2 model families of multiple sizes, we observe that, similar to the pre-training scaling laws, post-training task performance scales as a power law against the number of finetuning examples. This power law relationship holds across a broad array of capabilities, including mathematical reasoning, coding, instruction following, and multihop-reasoning. In addition, for tasks like math and multihop reasoning, we observe that a handful of examples merely align the model stylistically but do not saturate performance on the benchmarks. Model performance is instead correlated with its reasoning ability and it improves significantly with more examples. We also observe that language models are not necessarily limited to using knowledge learned during pre-training. With appropriate post-training, a model’s ability to integrate new knowledge greatly improves on downstream tasks like multihop question-answering.

This paper then provides evidence against the “knowledge base is formed only in pretraining” understanding. Traditionally (e.g. 2022), LLM training consists of pretraining, midtraining (on data of specialized domain e.g. STEM), instruction-tuning/SFT, and RL. Subsequently it’s becoming clear that focusing on SFT alone can provide has outsized returns:

- Models benefit from learning from QA data, if it’s high quality and have diverse prompt format

- The resulting model also learns how to act as an assistant (style alignment)

This style of training allows the introduction of additional tricks such as Rephrasing. First widely introduced in Llama3 and now used in more models like Kimi, to create more synthetic training data from existing data. This technique rephrases text in different ways, and creates question-answer pairs from this text in different styles. This can be thought of as a form of data augmentation, encouraging model generalization.

What about Style-locking?

In vanilla instruction-tuning, the model is shown the prompt, and generates the response tokens with the objective of matching the response token distribution with that of the reference response, while MASKING the loss of the prompt tokens. In other words, in instruction-tuning, the response generation is always conditioned on the prompt. A potential concern might be that this can degrade the model’s generative ability and learn to only output in question-answer format, such that if prompted something non-standard like “1, 2, 3, 4,...” it would shit the bed.

Yet another trick and observation regarding this is found in Instruction following without instruction tuning (Sept, 2024), associated blogpost. It found that:

Adaptations like training only on poetry, or only on responses without corresponding instructions, yield models that follow instructions. We call this implicit instruction tuning.

Language models are, in some sense, just really prone to following general instructions, even when our adaptation strategies don’t teach the behavior directly. We call this implicit instruction tuning.

In other words, training only on RESPONSES of QA-pairs would elicit proper instruction-following, which removes this concern of rigid style and degraded generative ability. This phenomenon is very interesting, as it’s not an obvious result. One potential hypothesis is that being able to predict the responses means the model would have to understand the context around them (i.e. “I’m likely reading a response to a question”).

So now, SFT can be simplified to: train on diverse and high-quality RESPONSES to QA pairs. Note here “quality” is essentially “long chain-of-thought” style text.

It’s great to see the field simplifying and focusing on what matters the most. A recent paper from Nvidia (Sep, 2025) investigates the interaction of data and phase of training, specifically,

Is adding reasoning data earlier during pre-training any better than introducing it during post-training, when the token counts are controlled? Could earlier inclusion risk overfitting and harm generalization, or instead establish durable foundations that later fine-tuning cannot recover?

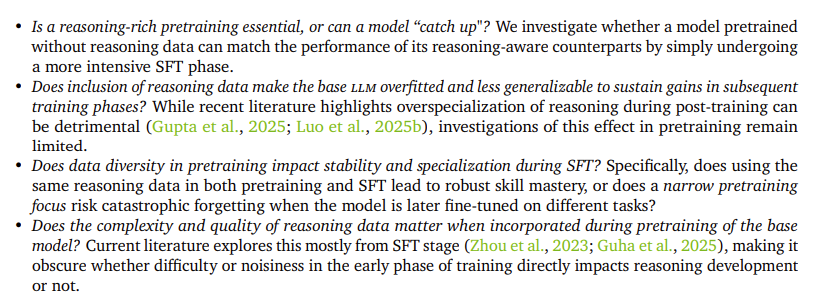

This paper investigates the following specific hypothesis:

with conclusions

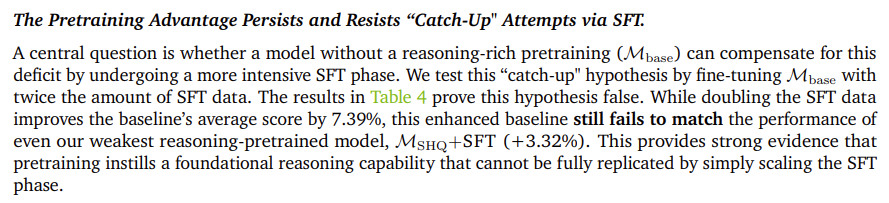

and most importantly refute the SFT-reasoning catchup hypothesis at the end:

This is unfortunate, as pretraining is often the most costly part of LLM training.

Note that the Nvidia paper still concludes that

SFT is a phase of targeted refinement, not broad data absorption

this is in direct conflict with the “Revisiting the superficial alignment hypothesis” paper, which concludes from new-fact learning experiments that:

if the model is first post-trained to do reasoning, it gets better at absorbing new information and using it in multihop reasoning tasks.

In terms of experiment setup, the Nvidia paper’s conclusion about SFT being targeted refinement seems weaker, as its conclusion derives from the observation that naively doubling SFT dataset with mixed quality data does not improve model performance compared to adding small amount of high quality data.

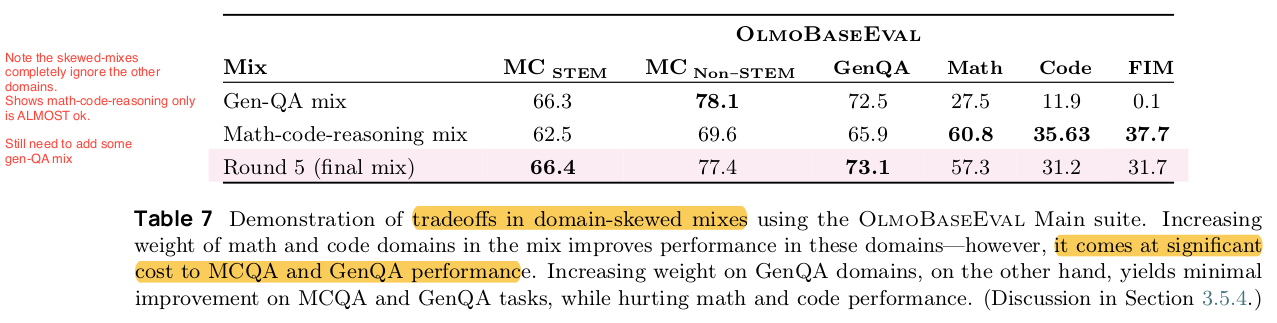

In a similar vein, the recently released OLMO3 showed a cool ablation study comparing the effects of including reasoning/stem data vs not into midtraining stage (total 100B tokens) and showed asymmetrical benefits of different data types to downstream model capabilities.

In conclusion, the basic intuition is the same:

- Pretraining data needs to be diverse and have a high scale. Having reasoning data is useful and raises the upper bound.

- SFT data needs to focus on high quality, and indeed, quality > quantity here.

The details are simplifying:

- Training on simply the responses of high quality SFT/Instruction-tuning data is enough to both elicit proper instruction tuning, model capability, and instill reasoning abilities, without degrading other general abilities significantly (e.g. creative-writing).

But perhaps even having a distinction between pretraining, mid-training, and SFT-post-training is an unecessary division. The only meaningful difference is just the learning rate. Perhaps eventually, the boundaries here will be blurred even more and dynamic learning-rate tuning will become the norm.

What underlying principle hypothesis can be used to explain these observations? Perhaps a good title for a review paper could be "The unreasonable effectivness of reasoning data".

- Models learn semantics, language distribution, and a naive world model from pretraining. Here scale and diversity is important because we want to sample the language distribution as widely as possible.

- Big problems with language models are hallucination and reliable long horizon reasoning – these abilities have lower entropy and requires higher generalization

- To combat this problem, we need lots of high quality (e.g. long COT, multi-hop, coherent reasoning) data.

- Yet the process is robust enough such that improvement in reasoning abilities doesn’t necessarily compromise higher entropy tasks performance significantly.

I suspect that language structure likely contributes to the unreasonable effectiveness of reasoning data!

But another explanation could simply be...almost all useful tasks and evals for LLM depend on having robust reasoning and applying them to construction and deductions from assumptions and given info, so it only makes sense that having more high-quality reasoning data in all stages of training benefits model performance 🤷♂️