Dec 5, 2025 - DeepSeekMath V2: Iterative improvement through self-verification

Table of Contents

DeepSeekMath-v2 came out on Thanksgiving without much fanfare but has now become the only open weight model to achieve IMO-gold performance with natural language informal proofs, after Gemini and GPT5. The technical reported is a packed with technical details, much of which isn't entirely surprising as the entire LLM field has converged toward a similar direction in terms of how to achieve iterative improvements in a domain like informal math proofs.

Key ideas

How to verify?

In the past year, RL with verifiable reward (RLVR) has made a lot of stride, especially in math and coding domains. After GPT-4o, Deepseek-R1 paper really popularized this approach (history repeating itself with DeepseekMath-v2 now). However, for something not easily verifiable like math proofs, how to craft a reward function that provides a training signal?

In other words, how to verify math proofs better to provide a training signal to improve proof generation?

Taking inspiration from human proof verification, we notice that:

- Issues can be identified in a proof even without reference solution. Whether this is by pattern matching a familiar subproblem and noticing a wrong solution, or by noticing inconsistent logical statement even if one cannot verify how the predicates and conclusion of a logical statement were derived.

- A proof is more likely to be valid when no issues can be identified after "thinking for a long time by a lot of different people". This is similar to the scientific peer review process. In LLM speak, this means that a proof is more valid if "after scaled verification efforts no issues can be identified".

So the answer to "how to verify better" is then "scaling verification compute".

What's "scaling verification compute"?

This is in line with scaling test time compute. In the case of DeepseekMath-V2, this is parallel inference with majority-voting, which does the following:

Given a proof, how do we verify its correctness better?

- Give the proof to the verifier model, ask it to evaluate the proof according to some rules.

- Do this in parallel for

times. - If most of the generated verifications think there's no problem, then proof is probably good.

- If at least

of the generated verifications think that there's some kind of problem, then proof probably has a problem. - If no group of

verifications agree on a correctness score, then the verifier is too unsure of the proof quality -- this means the verifier is not smart enough to check the work of that proof. We can discard this specific proof rollout.

How to improve proof-generation ability?

The verifier with scaled compute can now provide a reward signal to improve proof generation in an RL setting. This reduces to the classic RLVR-by-GRPO:

- For each problem

, generate proofs from the model. - For each proof

, do scaled verification (so times per proof), and get the resulting proof's score from majority voting -- this results in a set of { , } for each problem. - Combine each

with other rubrics to get a final reward score for . - Do backprop with the reward score.

The reward score for proof-generation is set to be

At the end of a round of RL, we can additionally do SFT for each problem

Maintaining generation-verification gap

An assumption that is implied in the above approach is that verification is easier than generation, this is known as the "generation-verification gap". This has the same intuition as P != NP -- the widely believed but unproven statement that problems whose solutions are easy to verify (P) are not necessarily easy to solve (NP).

Scaling verification compute to verify generated proofs by the LLM can work IF there exists a gap between the proof generator and the proof verifier. But as RL improves the generator, this gap shrinks and performance eventually saturates, and the rate of this saturation has been shown to correlate to the models' pretraining flops.

Therefore to continuously improve generator abilities, the verifier capability needs to improve as well -- in other words, the generation-verification gap needs to be maintained.

This means the verifier needs to be continously trained somehow, with dataset of {proof, proof score}. This was provided exactly during the proof-generation rollout process!

With this data, RLVR-by-GRPO for verification generation can proceed similarly. The obvious reward term is:

where

Additionally, there's format reward

Prevent verifier hallucination with meta-verification

With only

The underlying idea here is again the generation-verification gap -- it's easier to verify the verifications than generating the verifications. Here, for each verification, a metaverification is generated to find issues in the verification analysis with an accompanying verification quality score

In the end, the verifier can both verify proofs, and verify those verifications.

Meta-verification as an additional scaling axis?

All problems in computer science can be solved by another level of indirection [...] except for the problem of too many levels of indirection

The above is a a piece of engineering common wisdom that's also used often as a meme/joke. It's often applied in situations where the solution is to apply an extra layer of abstraction (e.g. virtual memory, file descriptors, DNS, abstract classes/interfaces, containers, etc). The use of meta-verification reminded me of this.

Metaverification here takes the advantage of the verification-generation gap. It's unclear how fast the metaverification-verification gap reduces compared to the verification-generator gap, and how that relative convergence varies for problem domains. Perhaps multiple layers of metaverifications can become a trick to prevent verifier performance saturation?

Alternatively, we can think of meta-verification as introducing additional layer of model "feedback-loop" to amplify its abilities.

Forcing self-verification during proof generation

The authors points out that

when a proof generator fails to produce a completely correct proof in one shot [...] iterative verification and refinement can improve results. This involves analyzing the proof with an external verifier and prompting the generator to address identified issues.

But in practice:

while the generator can refine proofs based on external feedback, it fails to evaluate its own work with the same rigor as the dedicated verifier

What this means:

- Scenario: The model generates a flawed proof.

- Standard Behavior: The model concludes "Therefore, the answer is X" and internally assigns it a high confidence.

- The Consequence: Because the model thinks it is right, it stops. It never triggers a refinement loop because it doesn't believe there is anything to fix.

While the model could fix the error if an external teacher pointed it out, it fails to find the error itself.

The authors then refined the proof-generation prompt and updated the reward function to force the model to rigorously "identify and resolve as many issues as possible before finalizing the response" (i.e. a type of test-time compute scaling by increasing reasoning chain length).

This is done by:

- In addition to the proof

generated, the prompt also asks the model to generate a self-analysis of the proof according to the same rubric given to the verifier. - The proof

receives score , and the self-analysis receives metaverification score .

The reward function then becomes:

So the verifier will check the proof generated, and the associated self-analysis. This then incentives the model to think harder and not be lazy.

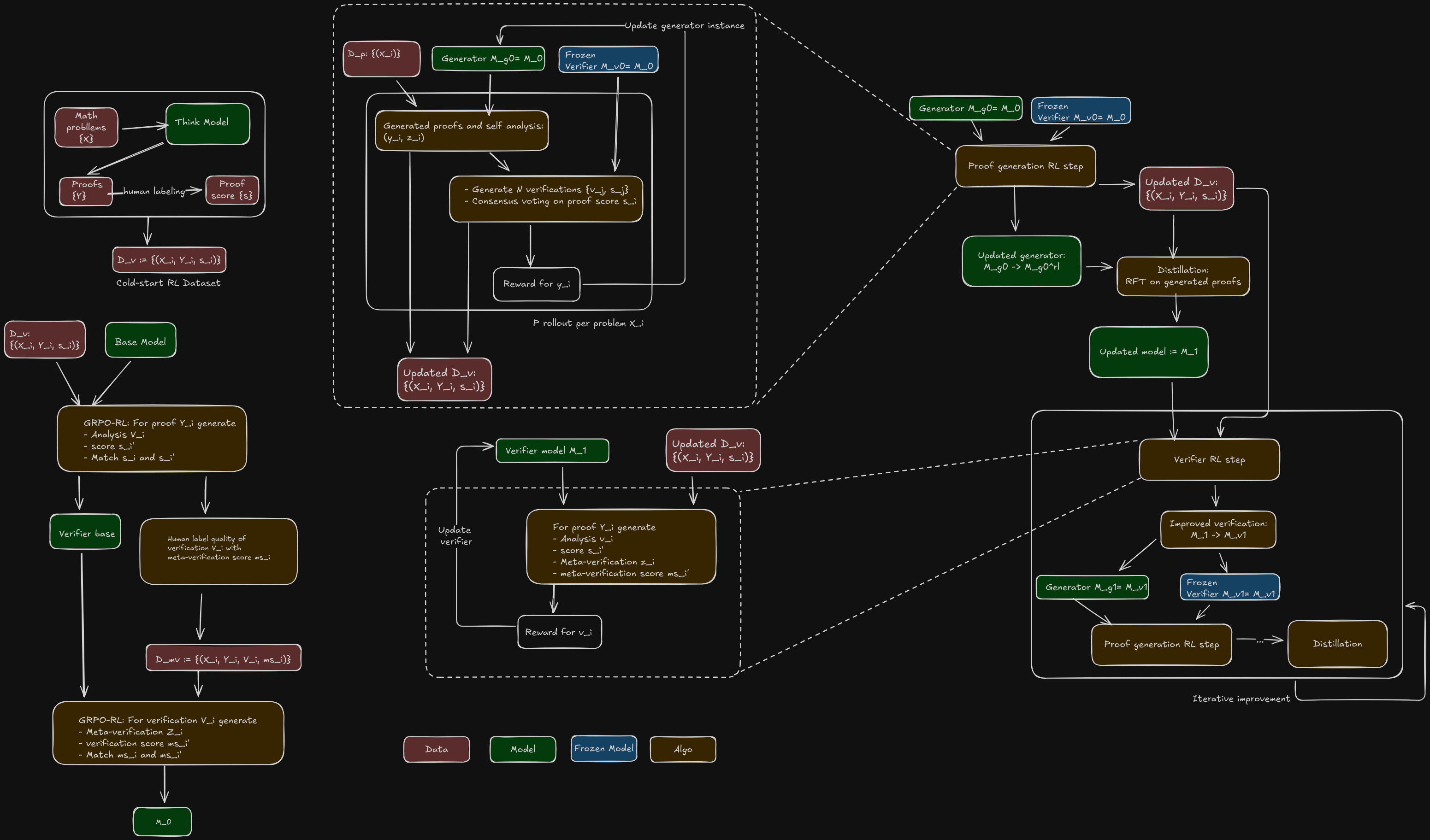

Iterative improvement

Now all pieces are in place to do continuous iterative improvement. Note that even though we talk about "verifier" and "generator", they are in fact the checkpoints of the same model. Let

In iteration 0, we have the following steps:

- Initalize proof verifier

from and freeze it. - Initialize proof generator

from . Use it for proof-generation RLVR with rollouts: - for each problem

, generate proofs. - for each proof

and associated self-analysis , generate verifications - Conduct consensus voting among the

verifications to either assign a score to each proof for reward calculation (and associated metaverification score for ), or discard that proof if no consensus.

- Conduct consensus voting among the

- for each proof

- backpropagate all the reward signals on the generated proofs and self-analyses.

- At end of each iteration, we also save

-- triplets of problem, proof, and proof score for verifier training. - After this process,

updated to .

- for each problem

- Do distillation via SFT on

with correct proof rollouts, i.e. subset of where , this gives us .

In iteration 1 and on, we have:

- Do verification-generation rollout with

rollouts on . - for each proof

, generate verifications and metaverifications - for each verification

, metaverification , and associated proof score , calculate reward score .

- for each verification

- At end of this process,

is updated to .

- for each proof

- [Not explicitly stated in the paper]: The metaverification ability can also be improved via RL here. For each

from the previous round, generate metaverifications and perform consensus voting to obtain "ground-truth" metascore . The RL process reward metaverification rollout metascore to match . - Freeze

. - Initialize proof generator

from . Do proof-generation RLVR with rollouts. After this step, becomes . - Do SFT on

with correct proof rollouts, resulting in .

Important details

Model initialization and cold-start

Before the iterative improvement can begin, SFT is needd to improve the baseline generation and verification performance -- otherwise a lot of inference compute would be wasted to derive easy facts. Fortunately the base model DeepSeek-V3.2-Exp-Base already has reasonable math capabilities.

Cold-start verifier RL dataset

To start verifier RL training, a set of hard problems, proofs and estimates of proof quality is needed.

- Curate

by crawling hard math problems (e.g. IMO, USAMO, CMO, etc) that require proofs. - Generate candidate proofs using Deepseek-V3.2-Exp-Thinking -- a capable thinking model. The prompt used iterative-refinement to ask the model to improve its proofs to improve the proof quality.

- Sample from this pool of generated proofs and have humans annotate the proof quality.

This process yields the initial RL-dataset

Cold-start metaverifier RL dataset

Similarly, annotations are needed to initiate RL training for the metaverifier.

- The verifier generates proof verification

( is part of this) for proof . - Human experts annotate

according to some rubric to arrive at a verification score, . - The resulting dataset

is used to train the metaverifier (same as the verifier) to produce a summary of issues found in each verification and produce a verification score to match .

Inference: Sequential refinement with verification

Iterative self-refinement is a test-time inference scaling idea introduced around 2023 (self-refine, ReAct). This technique is similar to how humans try to iteratively refine a solution:

- Model generates an answer

- Prompts the model verifies and spots mistakes in the answer and proposes solution

- Prompt the model to generate an answer again, taking into account of its own analysis in (2).

- Iterate 2-3 multiple times

Notice with this method, while the quality of the proof improves with additional iterations, its ultimately limited by the verifier's ability!

The process of iterative self-refinement can additionally be parallelized (i.e. having multiple people thinking about the same problem repeatedly). The final answer can then be determined by committee among the different threads' answers (i.e. via majority voting, another synthesizer model decided based on their results, etc)

High-Compute Search (Population-Based Refinement)

For the most challenging problems where standard sequential refinement fails, the paper proposes a "High-Compute Search" that scales both generation (breadth) and verification (depth). Instead of refining a single thread, this method evolves a population of proofs.

- Initialization: A pool of candidate proofs is initialized (e.g., 64 samples).

- Mass Verification: For each proof in the pool, the model generates 64 independent verification analyses. This statistical volume helps identify subtle issues that a single verification pass might miss.

- Selection & Pairing: The system selects the 64 highest-scoring proofs based on their average verification scores. Each selected proof is paired with 8 verification analyses, specifically prioritizing those that identified issues (scores of 0 or 0.5).

- Evolution: Each

<proof, analysis>pair is used to generate a new, refined proof, which updates the candidate pool. - Termination: The process repeats for up to 16 iterations or until a proof passes all 64 verification attempts (unanimous consensus), indicating extremely high confidence in correctness.

This method is used to eventually take IMO 2025 and Putnam 2024 achieving incredible scores.

Step 3 seems rather strange -- pairing high-scoring proofs with randomly sampled verification you are bound to end up with <proof, analysis> pairs where the analysis is simply irrelevant to the proof. I wonder how often this actually generates a better proof than the existing pool, in other words, how compute efficient this is.

Why this works and what next?

The success of AlphaGo and AlphaZero were major inspirations for a lot of the iterative improvement approaches. But the approaches there are hard to translate into iterative improvement in LLMs, as previously explained in DeepSeek-R1:

we explored using Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) to enhance test-time compute scalability. This approach involves breaking answers into smaller parts to allow the model to explore the solution space systematically. To facilitate this, we prompt the model to generate multiple tags that correspond to specific reasoning steps necessary for the search. For training, we first use collected prompts to find answers via MCTS guided by a pre-trained value model. Subsequently, we use the resulting question-answer pairs to train both the actor model and the value model, iteratively refining the process.

However, this approach encounters several challenges when scaling up the training. First,unlike chess, where the search space is relatively well-defined, token generation presents an exponentially larger search space [...] Second, the value model directly influences the quality of generation since it guides each step of the search process. Training a fine-grained value model is inherently difficult, which makes it challenging for the model to iteratively improve.

In conclusion, while MCTS can improve performance during inference when paired with a pre-trained value model, iteratively boosting model performance through self-search remains a significant challenge.

The MCTS in AlphaGo/Zero was hard to replicate because:

- The LLM token space is hard to define as a search problem useful for MCTS.

- The value function used to guide the search is hard to define.

GRPO-style RL solves (1) by replacing tree search with parallel sampling (exploration), and applying the same to verification solves (2) by using verifiers as the reward model. Now, iterative improvement is possible.

The core mechanism in both systems is using compute-heavy search to generate high-quality data, then distilling that data back into the model to improve its "instinctive" capabilities.

| Component | AlphaGo / AlphaZero | DeepSeekMath-V2 |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Search Guide (The "Intuition") |

Policy & Value Networks Neural networks that predict the best next move ( |

Verifier Model A model trained to estimate the correctness of a proof ( |

| 2. Search Mechanism (The "Thinking") |

Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) Simulates thousands of future game trajectories to refine the probability of which move is truly best. |

Parallel Sampling & Refinement Generates multiple candidate proofs (Best-of-N) and performs iterative self-correction to find a valid solution. |

| 3. Policy Improvement (Improving Generation) |

Distillation of Search Probabilities The Policy Network is trained to match the move counts from MCTS (learning to instantly predict moves that took MCTS a long time to find). |

Rejection Fine-Tuning (RFT) The Generator is trained (SFT) on the successful proof rollouts found via high-compute search/refinement (learning to instantly generate proofs that required iterative fixing). |

| 4. Value Improvement (Improving Evaluation) |

Training on Game Outcomes The Value Network is retrained to predict the actual winner ( |

Training on Consensus Verification The Verifier is retrained to predict the consensus score derived from majority voting (grounding its estimates in statistical consistency). |

It's obvious that iterative improvement for a verifiable domain like Go should work. The intuition behind why it should work for a hard-to-verify domain like math proofs is less so, and I understand it as the following:

- Consensus Voting as Noise Reduction Individual model outputs are noisy samples from a probability distribution. By sampling

verifications and taking a majority vote (especially when cross-checked by a Meta-Verifier), we effectively reduce the variance.

- The "Consensus Label" is a far higher-fidelity approximation of the "Ground Truth" than any single model inference.

- Training on this consensus effectively "denoises" the model's understanding of what constitutes a valid proof.

- Known in the field as "self-consistency" - Manifold Expansion via Search and Distillation We can view the "space of correct mathematical proofs" as a low-dimensional manifold within the high-dimensional space of all possible text.

- RL/Search (The Reach): Standard generation samples near the center of the model's current manifold. Iterative Refinement (Test-Time compute scaling or multiple rounds of RL) allows the model to traverse off its comfortable manifold, stepping through error-correction to find a distant solution point (a hard proof) that it could not generate zero-shot.

- Distillation (The Pull): By performing SFT/RFT on these distant solution points, we pull the model's base distribution (manifold) towards these new regions

- The Result: The "center" of the manifold shifts. Problems that previously required expensive search (edges of the manifold) are now near the center (zero-shot solvable).

- The Difficulty Ceiling As the model improves, the manifold covers the entire training distribution. The limiting factor becomes the difficulty of the problems. If the model can solve everything in the dataset zero-shot, the gradient for improvement vanishes. To exceed the best human capability, the system eventually needs a mechanism to generate novel, harder problems (synthetic data generation) or prove open conjectures where the ground truth is unknown, relying entirely on its self-verification rigor to guide the search into uncharted mathematical territory -- this is likely needed for "superintelligence".

This intuition is well-observed in human learning: we improve the fastest when we are attempting tasks that are SLIGHTLY out-of-reach. In fact, the "search" and "verifier" in LLM iterative improvement are analogous to "information" in the Challenge Point Framework for optimal learning difficulty.